There’s no denying the appeal of converting an old $100 (or even a new $700) wood stove in to a sauna heater. For many of us there is a huge bit of accomplishment and joy in producing something ourselves. Many of us like the solid look of heavy steel. And saving $2k isn’t bad either.

But there’s a problem. I’ve never seen such as conversion or even a build from scratch actually work. The resulting stove heats us and the room, it makes steam, …but it doesn’t result in what people in Finland call a sauna. It’s just a hot room which is very different from a sauna.

- A sauna is gentle indirect convective heat, while our homemade stove is producing a lot of the radiant that is undesirable in a sauna.

- Steam in a sauna is gentle but intense steam made from water on stones, while our DIY project produces steam from steel that’s hotter, kind of stings, and stays up around our heads instead of evenly enveloping our body.

The Functions Of A Sauna Heater

Ask any person who’s grown up in Finland what the best sauna is and they will quickly reply ‘smoke sauna’. The goal of any sauna heater then is to produce a room environment and bather experience as near to that of a smoke sauna as possible. And this is no easy task.

To produce this sauna environment a sauna heater then has four primary functions;

- Heat a mass of stones.

- Have airflow up through the stones that heats bathers with convective heat.

- Produce steam from water poured on the stones.

- Produce as little radiant heat as possible.

These are the goals for a sauna heater. Achieving them is not easy and is parts science, art and tenacity.

The Stones

The stones (including Kerkes) are a necessary required element for something to be a sauna – to create the unique environment of a sauna.

First is airflow up through the stones that heats bathers with gentle indirect convective heat. This heat is more even and more comfortable than convective heat made from steel or other sources.

Second is producing gentle but intense steam from stones. This steam is different than steam from steel. Stone steam caresses us more evenly on every inch of our body while steel steam is often both hotter and remains compressed (greater density in addition to being hotter) up around our head and shoulders.

Hot stones allow us to create whatever steam we prefer. We can pour water in one place to have a slower gentler steam, shower it all around the top stones for a more intense steam or place ice balls on the stones that slowly melt producing a more humid bio-sauna environment.

Stones produce steam with negative ions that enhance our mood while the positive ions of steel steam increase feelings of fatigue, anxiety and depression.

Finally, stones are a natural element. Both the convective heat and steam from stones connect us to nature. Steel is a man-made substance that does not provide this connectivity. Steel produces extra hot biting steam but leaves us with a cold relationship to nature.

A Wood Stove Conversion

To see why it is so difficult to make our own and why sauna heaters from Finland are made the way they are (See ‘Heater Design’ on Trumpkin’s Notes on Sauna Heaters.), let’s look at a purpose built wood stove conversion – a Kuuma.

1) Heating The Stones

Goal number one is not an easy task. Kuuma is a wood stove conversion that is purpose built to be a sauna heater, and it fails to heat the stones.

On the one below, the hottest I found was 146°c while most were 97-108°c (and this is typical of every Kuuma I’ve measured). Stones need to be a minimum of about 120°c to make steam with about 150-300 the desirable range for good löyly. Similar to other Kuuma’s this resulted in steel steam (from the top of the fire box instead of stones) that stings and was ‘biting’ rather than the gentle but intense steam that is generally most desirable in a sauna.

The primary cause of this is likely that much of the heat produced by the fire becomes radiant heat which means that it’s not available to heat the stones. Heat takes the path of least resistance and here that path is in to the welcoming heavy steel carcass and then radiated outward. The stones are a more difficult path and so require considerable design work to direct the heat in to them.

Sauna heaters are made with thinner materials and design elements that make the stones the path of least resistance.

2) Indirect Convective Heat

Assuming we figure out the stone heating challenge, our next goal is airflow up through the stones to produce the convective loop that heats bathers with gentle indirect convective heat. This one shouldn’t be too difficult. The key is exposing the air to as much heated stone as possible as it rises up through them. Typically air is introduced in to the bottom of the stone chamber in a way that it disperses and flows up through the stones. Here’s how one heater from Helo does this:

The Kuuma has no airflow at all. I think simply because they didn’t understand the purpose of the stones and how critical this airflow is.

Someone building their own can now know that they need considerable airflow up through the stones.

3) Stone Steam

Good steam from stones is essential to sauna.

Stones store a lot of energy (heat) and release it slowly. Steam made from stones is typically 100°c (it takes a lot of extra energy to break through to the higher ‘superheated’ temps) and fairly quickly begins to disperse evenly down along our body.

Steel steam is likely superheated to above 100°c which feels noticeably hotter, it sticks higher up around our head and shoulders resulting in a higher concentration that feels hotter still, and does not descend downward well so there’s a much greater head to toes difference than with stone steam.

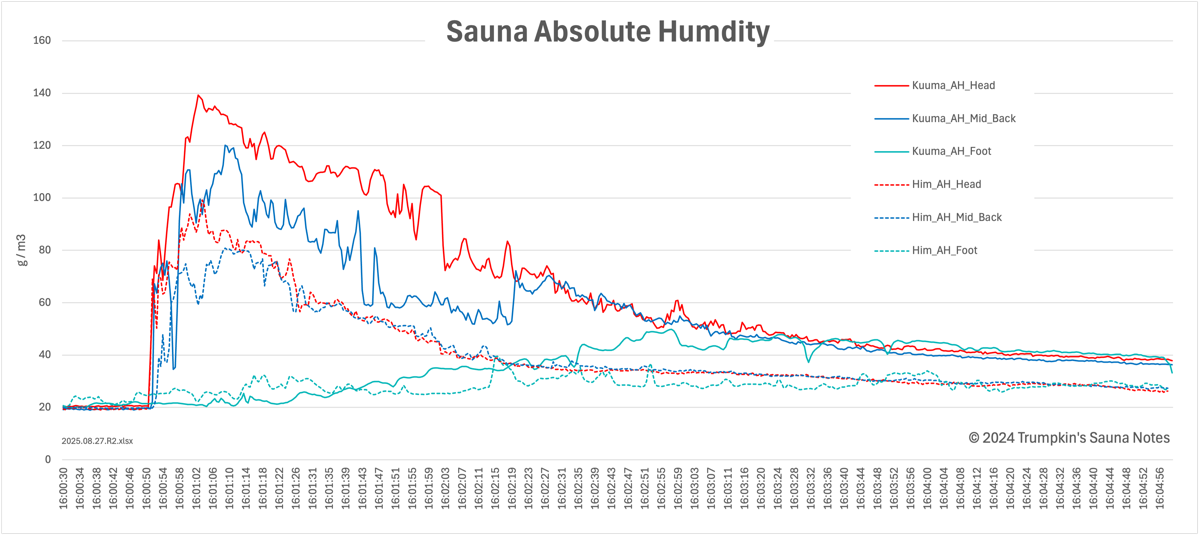

This chart compares steam made from stones (Him_) and steam made from steel (Kuuma_). In both cases the steam was created with approximately 300ml of water. The Helo Himalaya was from one 300ml ladle while I had to do three ladles, one after the other, of 100ml each for the Kuuma which resulted in three tranches of steam about 5 seconds between each.

Let’s look at the three phases of the temporal envelope;

- Attack – The attack appears similar but would likely have been faster with the Kuuma had I used a single 330ml ladle.

- Peak – The peak on the Kuuma is higher for a couple of likely reasons; 1) the steam is hotter and more buoyant so sticks near the ceiling for longer while the stone steam begins dispersing downward almost immediately, 2) the steel plate is more efficient and likely to convert more of the water to steam vs the Himalaya that likely only converted maybe 80% with the other 20% either becoming fog or water on the floor.

- Decay – This is the big difference. The stone steam begins to disperse almost immediately (the red (head) and blue (mid_back) lines come together quickly). The steel steam remains stratified for a considerable time with a greater concentration around our head and shoulders, and less below our shoulders.

The experience matches this. The steel steam is noticeably hotter (we also created steam once with only a single 100ml ladle on the Kuuma and it was still stinging hot). Just as the chart indicates it also stayed around our head and shoulders for longer before it began to disperse downward.

This increased stratification of the Kuuma steam is noticeable (as is the lack of steam around our feet in both).

The causes of this appear to be;

- The stones aren’t hot enough to produce much or any steam from the water poured on them. Stones need to be about 120°c or higher to produce much steam at all but realistically well above 150-200°c to produce the steam needed for a sauna. Since the water isn’t converted to steam, it flows downward.

- A lack of stone depth. Even with much hotter stones a good sauna heater needs a depth of about 35cm (14”) top to bottom to produce steam. Less depth, like the 16cm (7”) for the Kuuma, means that more of the water isn’t converted to steam and instead reaches the steel top of the firebox.

- The firebox top is flat so the water has no place to go except to lay there and become steel steam. A sloped, peaked or rounded element would allow some of the water to flow off before becoming steel steam.

For an in-depth look at steam in a sauna: Why Sauna Designers Should Care About The Law Of Löyly.

4) Minimal Radiant

Perhaps the most unique aspect of a sauna compared to other sweat bathing experiences is that we are heated primarily and almost exclusively by gentle indirect convective heat.

For more see: Radiant – To Be Or Not To Be.

This may be a greater challenge than heating the stones and is also directly related to it.

Zero Sum Game – Heat is a zero sum game. Any heat that becomes radiant is heat that is not available to heat the stones. This isn’t an issue of simply blocking the radiant heat, but an issue of designing the heater from the middle of the fire out to direct heat to the stones and not to the carcass.

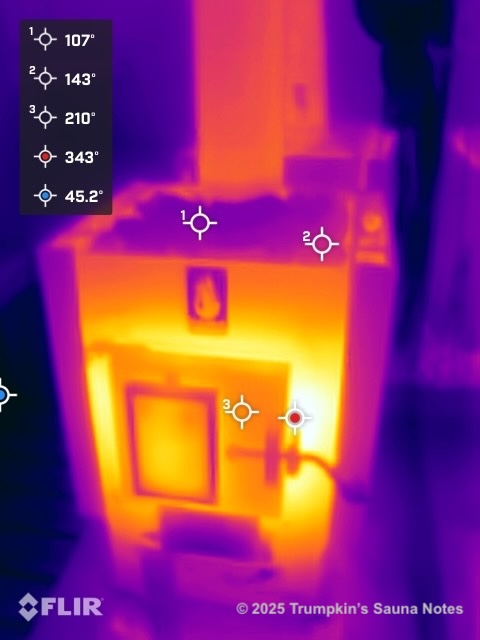

The heat shields work OK from the sides. We still felt a lot of radiant on our faces and lower legs from every seating position however. As Lassi noted, this probably from the face of the stove that has a lot of very hot thick steel. The flue @ 164°c might have produced a little bit of noticeable radiant as well though likely very minimal.

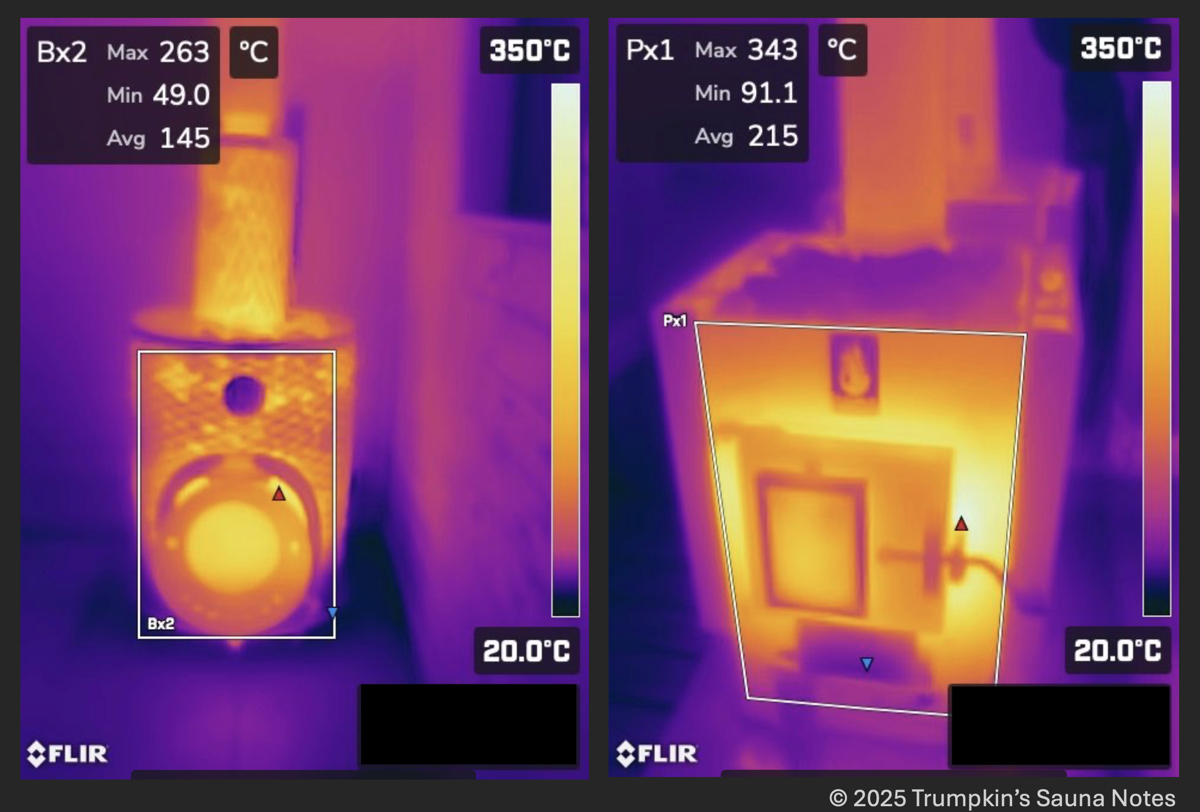

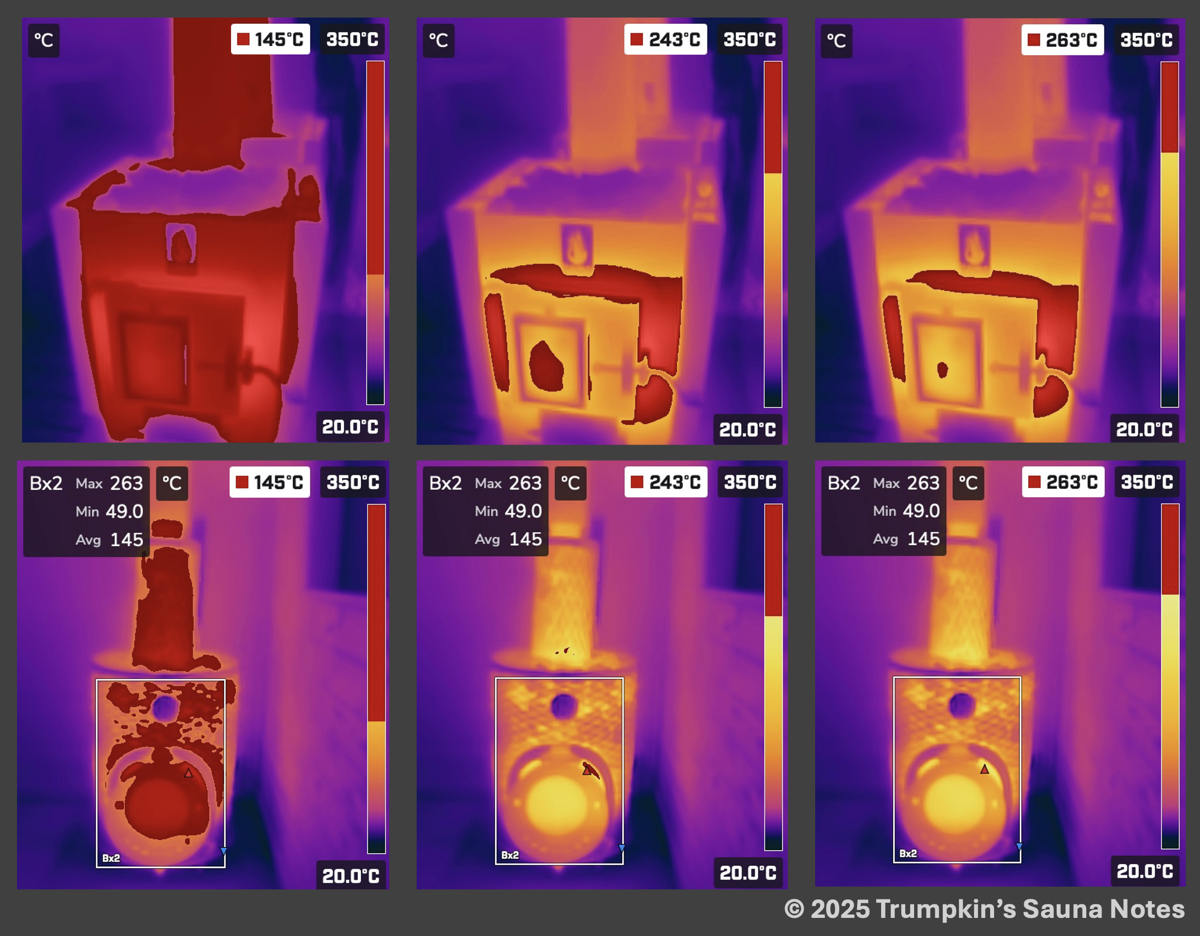

In comparison, an Iki Original has hotter stones and produces less radiant for a similar sauna head temp (90°c when this image was done). Note that the hottest point w/ this Iki is 261°c down in the stones near the flue. The Kuuma is a higher 350°c on its face which is also a large area of steel plate on the front.

Here’s a comparison of the heat produced by the face of an Iki vs Kuuma.

While an Iki produces much less radiant generally, the real standout is comparing how little of the Iki produces anything 243°c or higher compared to how much of the Kuuma is over 263°c. 263 is the hottest point on the Iki.

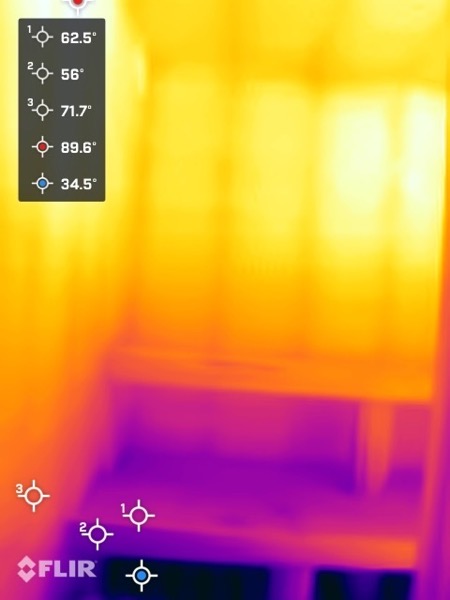

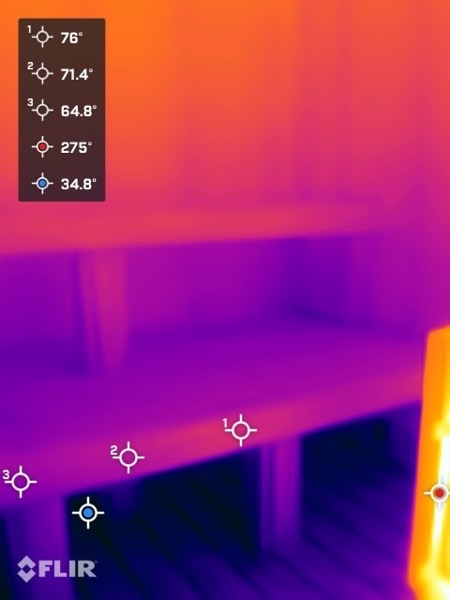

In these next two images we can see the radiant along the front of the foot bench with the signature radiant horizontal falloff. FWIW, the ambient air temp @ about 5cm above the foot bench was 58°c.

This first one shows the Kuuma stove and part of the foot bench. In a normal sauna with less radiant from the heater the temps along the front of the foot bench will largely be identical across the entire width and the same as the ambient air temperature. So here these would all have all been ≈ 56.5°c. The hottest point on the face was 81°c according to FLIR so about 24°c (43°f) of radiant.

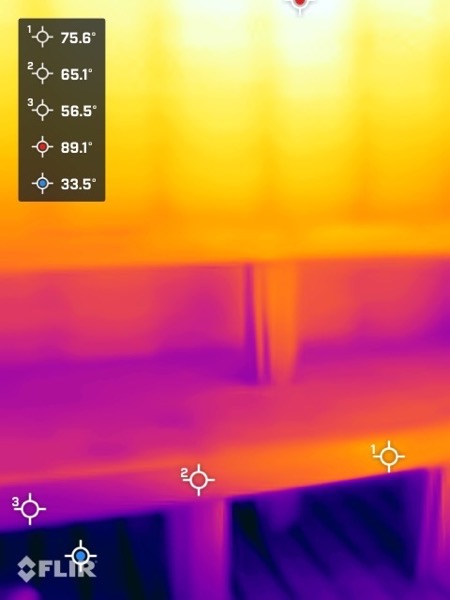

This second one shows a wider view of the foot bench. Point #1 is approximately the same in this and the prior image (color scales are different). The falloff from 75.6°c to 56.5°c is greater than would be expected based on inverse square law calculations which indicate about 71°c for this distance rather than 56.5. This however is due to the oblique angle.

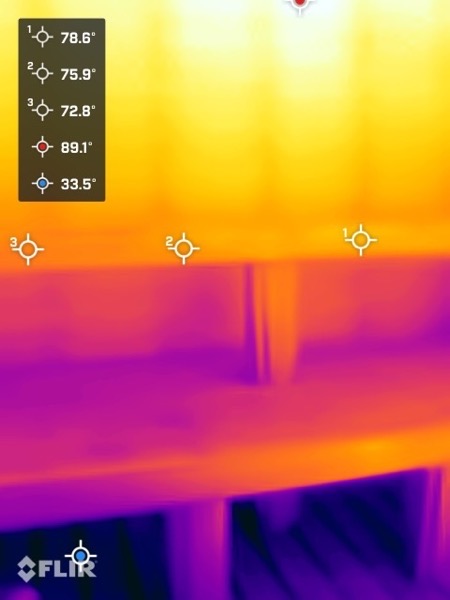

And here the temps on the face of the sitting bench. Again we see the telltale radiant signature of horizontal falloff as we get further from the stove. I was surprised there was this much effect from radiant here. The hotter ambient temps here moderate the falloff somewhat.

Ambient air head temp (official sauna temp) averaged ≈93°c for the time we were there. The head temp at the wall surface was 86°c which is slightly higher than would normally be expected for a 93°c ambient air temp, but this likely due to good insulation (plus warmer temps outside).

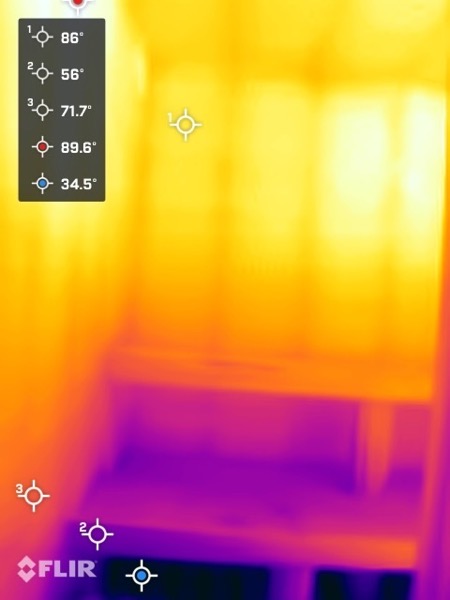

Two critical things to notice in this next image. The face of the foot bench is 56°c which is about what ambient air temp was at that strata and measured at 59°c just above the foot bench.

The wall to the left of the foot bench however is 71.7°c. This is due to radiant heat from the Kuuma that’s hitting it nearly perpendicular. Normally the wall would be slightly cooler, about 52-54°c perhaps, than ambient air temps and the bench due to energy loss to outside.

Here I moved point #1 down to the top of the foot bench where it’s indicating about 62.5°c. I’m not sure why this small area is so much hotter. I don’t think conduction. Likely radiant reflection from the wall on the left? A brief downdraft of hot air is also possible though not probable?